Yuri Kalendarev

Hans Gercke

Project BREAD AND LIGHT. Contemporary Art Museum. Sopot, Poland

PROJECT FOR SELTENLEER, "Blue - Color of Distance". Heidelberger Kunstverein, Germany

On the works of Yuri Kalendarev

Moat of Heidelberger Castel. Replanted stones from Seltenleer prison tower. Blue Island in background. |

Moat of Heidelberger Castel under Seltenleer prison tower. Replanted Blue Island. Blue quarzite, approx. 1,5 ton |

Monuments – here we are speaking above all of war and soldier monuments – glorify, idealize, aestheticize. They personalize historic extents whose criminal and inhumane substance is intentionally swept under the carpet of “great” epochal history. By monumentalizing, they make it insignificant: Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.

They are worthless as far as critical reflections on what people have done to other people and continue to do and what they are generally capable of doing.

Do we still need monuments today? In view of what has just been intimated, the answer can only be: no. We do not need a stone memorial that claims to keep the memory alive and is nothing more than a tombstone that assures us soothingly that this is all past and thus can no longer be changed anyway.

Can there be monuments today? The answer, I think, must likewise be: no.

When talking about war and all the crimes connected with it (or weren’t there any, just because we call it “war” – in Latin “Bellum”, beauty?) mustn’t every attempt to react to it with the means of art fail? Neither does it makes sense to “arrange” the gruesome happenings as a horror scene, nor to “overcome” them through an overly exalted monument. After Auschwitz, as Theodor Adorno proclamed in 1951 – as far as this theme is concerned – art is no longer possible. Whoever has visited Auschwitz will confirm this: the well-intentioned memorial in Birkenau is not only superfluous, but downright embarassing. What the remains of the reality there express about what happened at that place need nothing, but really nothing else added.

A memorial for the holocaust? This idea, too, is well-intentioned. Le Corbusier once stated that good intentions are the opposite of art. In any case it is a fatally mistaken beginning to want to react to the “monumentality” of the crime with a monumental design. As an exception to the rule one could be forced to agree with Chancellor Kohl who spoke out vehemently against the planned monument - even though he has proven elsewhere that he is no way the expert he thinks he is when it comes to monument discussions.

The second reason why there can be no more monuments today lies in the character of contemporary art. One of its specific features is that it does not allow itself to be instrumentalized. Contemporary art evades the function of mediating predetermined, verbalized contents.

It is conceivable only as an individual, subjective involvement with certain happenings or a certain place. Such an artistic involvement can be very precise, especially in its formal structure, yet at the same time remain open or ambivalent, with many meanings or layers of meaning with respect to what it has to say. This openness presents a challenge to the viewer to form his own thoughts. It is useless for patrons to try to put across a message “to the masses” with the help of art.

This is the point where Yuri Kalendarev starts out. His “antimonuments” are an extremely complex confrontation with history and topography both in a formal sense as well as regards contents. They can be experienced as autonomous aesthetic events which, however, retain their reference character, they incite one to think about the character of the particular place, they give impulses for thought whose results might possibly add a new dimension to the sensual experience.

Yuri Kalendarev’s art is minimalistic and epic at once – this only seems to be a contradiction. Whereby the epic side – the bringing together of the most various kinds of creative means and substantial points of reference – perhaps has something to do with the artist’s Russian heritage, whereas, in contrast, the minimalistic linking of diverging aspects carries more intellectual, even sophistic features, possibly from the other source that Yuri Kalendarev draws from, his Jewish tradition. This is not meant, however, to be an attempt to classify Kalendarev’s work in pigeon holes.

“The last catalogue of the works of Yuri Kalendarev was headed by one word: stones. He is a sculptor, quarry man, stonemason”. With these words Alexander Borovsky began his prefacing text on Kalendarev’s St. Petersburg exhibition “Column of Light”, in which a project was introduced that draws a connecting line between the “Bastille of the Tsars” (Zayatchiy Island and the Peter and Paul Fortress) and the Stalinistic concentration camp on Goltzy island, 500 kilometers north of it in Lake Onega.

Yuri Kalendarev has come a long way since his early stone sculptures with his current conceptual projects which can be designated more as Land Art. Stones are, of course, still of consequence - only the way that the artist deals with them has changed fundamentally – though successively, continually and consistently.

At the beginning was the physical, handworked, sweaty labor with this material – petrified, layered and crystallized over millions of years, preserving time and change in its very substance – with time this material constitution, its age, its non-man-made beauty gained in meaning and power of expression for the artist. Kalendarev started reducing his intervention in the material, more and more frequently he left the stones – almost – as they were, but found new creative possibilities in relocating and rearranging them by inventing apparently natural landscapes out of them and with their aid he drew attention to places of specific significance, produced lines of reference between nature and the work of man, between past and present – for instance in Tefen/Galilee (1986-1990) and in Louisville /Kentucky (1989) – in the tradition of ancient stone settings.

Here, in the case of the historical waterworks on the banks of the Ohio River, Yuri Kalendarev integrated sounds into his working concept for the first time, so that the list of materials of this work reads as follows: “Historic Site, Kentucky Field Rocks (approx. 20 tons), Blue Quarzite (approx. 1,5 tons), Kentucky Blue Grass, Water, Resounding Sound (Samuel Barber, Adagio for Strings)”.

The complexity of the materials is astounding (material and ‘‘immaterial”, organic and inorganic, constructed and grown), astounding too the meaning that the color blue has for Kalendarev, the ‘‘color of distance”, which has materialized in an incomparable way in Brasilian quarzite - seldom found - one of the hardest minerals of the earth.

This material, which he obtained himself from quarries in Bahia, played an important role in the piece ‘‘Seltenleer” (Seldom Empty), that Yuri Kalendarev staged in the park of the Fleidelberg palace, during the exhibition ‘‘Blau - Farbe der Feme” (Blue - the Color of Distance), sponsored by the Heidelberg Kunstverein in 1990 and which remained in place for several months, consciously including the changing of the seasons and the change of vegetation in his concept.

The Heidelberg work takes up a key position in Kalendarev’s oeuvre as it includes hewn sculpture elements as well as the opening into Land Art. Originally, ideas were already expressed here that were later perfected in Kiel and St. Petersburg. The ‘‘Seltenleer” was prison and one of the elements of the Heidelberg staging was called “Shelter”.

It is well-known that works of sculpture today reflect their context more strongly than was true even a generation ago and are considered as objects in a space – not only in a formal sense. The range of possibilities is uninterrupted for the ‘‘autonomous” sculpture which nonetheless changes its character in interaction with its location, extending to temporary or permanent installations of an artistic field in which historical or other models become the starting point on even a part of the meaning.

During the past decades Yuri Kalendarev’s art has developed decisively in the latter direction – with very specific key points:

1. He is fascinated by the historic significance of a place whose concealed or forgotten quality he lays bare and raises, through artistic accentuation, onto a conscious level. The kind of involvement is very personal, he is not concerned with a literary pictorialization of past events and not at all with that problematic dimension of monumental- like qualities mentioned at the beginning of this essay.

2. Kalendarev is satisfied with minimal interventions in the material which usually leave the substance of the original material intact, but he preferes to distribute these interventions over an extensive terrain. We have already mentioned the dialectics of the laconic and the epic as being characteristic of his art.

3. He is interested in creating connections between diverging aspects whose complex interrelatedness is thematized in his work. Thus a field of relationships arises that, in the extreme case of an immaterial kind, does not become concrete as a sculptural-spacial work except through the experience, through the empathy and through the reflection of the viewer.

For his contribution to the Heidelberg Blue Exhibition Yuri Kalendarev, with the aid of a blue bridge that could not be walked on, again used material means to connect different places, whereas in his St. Petersburg project he simply exchanged concrete materials, and in Kiel he was satisfied with the immaterial marking of two points that lay far apart and which he set in relationship to each other through the elementary means of light and sound. In addition come writing, water, air and movement. And not lastly through the polarity of the scenic-dramatic (Kilian) on the one hand and the static “illumination” (Nicolai) on the other hand, a spiritual bridge arises whose color, characteristically, is blue.

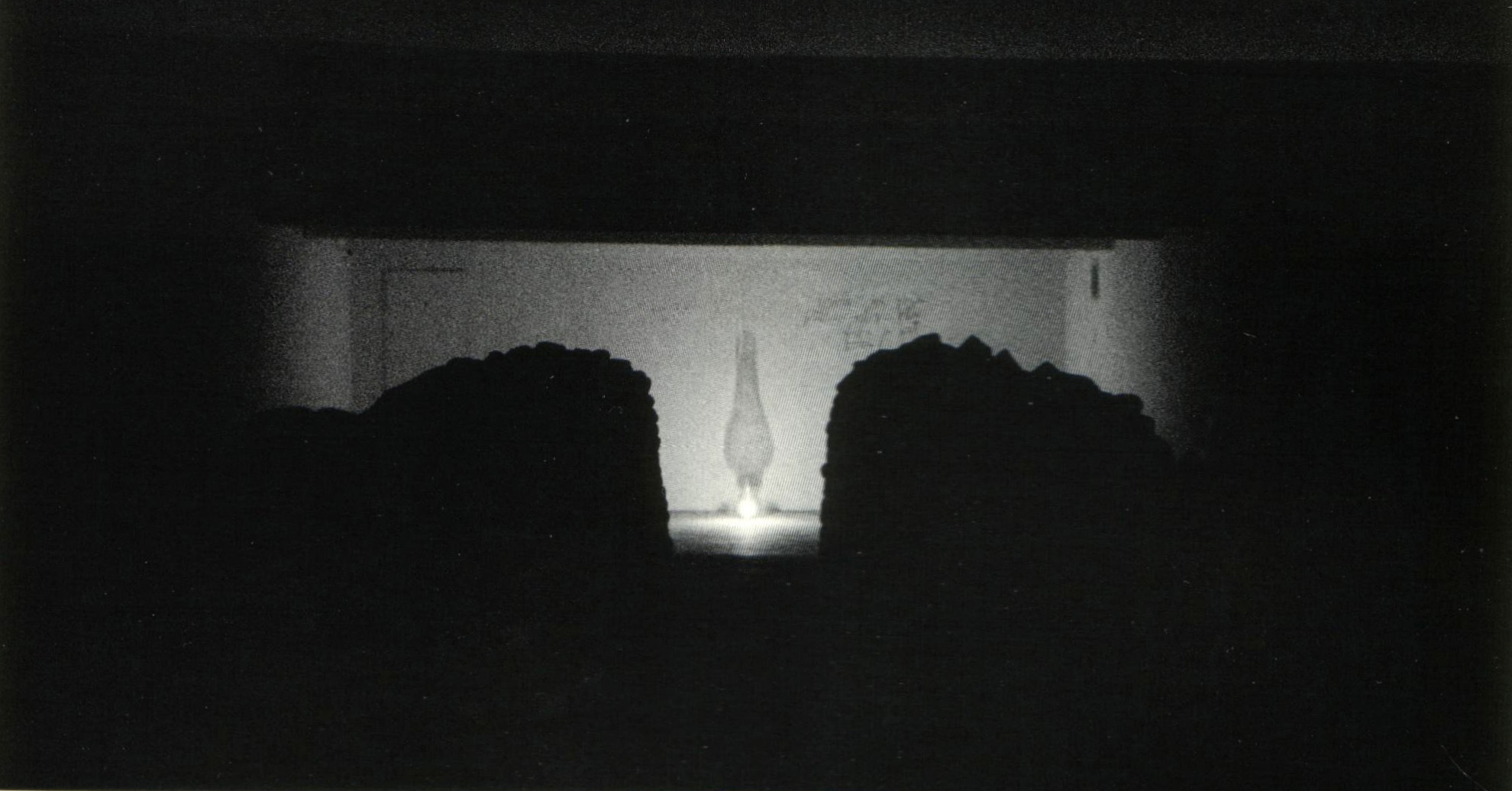

On our way to the Kiel work, which is described extensively on the other side of this publication, we would like to mention the stations in the big travelling exhibition of artists from St. Petersburg in which Yuri Kaléndarev has realized other aspects of his St. Petersburg theme in correspondingly new ways. Here too diverging work elements are set in relationship to one another which, altogether, indicate implications of contents: nature, the bombshelter-like room, the extinguished lamp of the forced laborers that takes on a new form as a gigantic shadow through a newly ignited light, mountains of bread that look like rocks and that fill the exhibition building with its fragrence.

Yuri Kaléndarev named this work “Requiem” and added the following text in Russian, Hebrew and English:

“Blessed are you, Lord our God, King of the Universe, who brings forth bread from the earth”.

Heidelberg, July 1995.

|

6,000 loaves of black bread piled together in six big rectangular blocks. |

Note: View of the exhibition space with the “Requiem ” installation in the State Gallery of Art in Sopot, Poland, 1995. The main part of the installation consists of 6,000 loaves of black bread piled together in six big rectangular blocks. The “Requiem” is related to the “Column of Light” project for Saint Petersburg, dedicated to two islands, two places of imprisonment. One island, with the fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul, together with the surviving imperial prison, the “Russian Bastille”, is located on the Neva river, in the centre of the city of Saint Petersburg. The other one, the Goltzy island, is on the Onega lake, 500 kms. north of Saint Petersburg and was a “Straf Lager” (a punishment camp) for punishing GULAG prisoners in Stalin’s times. Prisoners on this island were forced to carve granite and were destined to slowly die of starvation. The daily portion, “paika”, of the prisoner’s bread was related to his ability to produce a certain amount of stones a day, which were piled in big rectangular blocks, the so-called “paika”.

Translation: Katherine Funk-Roos, Meerbusch.

|

BREAD AND LIGHT. The Corner. Fragment. Loaves of forth black bread lit by pulsating blue strobe light at 90HZ per second. |